Some Reflections

The Radio Security Service achievements include:

1. It identified the Abwehr and allied organizations, how they worked and what influence they had on the conduct of the war.

2. It told us what the Germans were prepared to believe and what they did not.

3. In what areas the enemy lacked knowledge and where it did have accurate information.

4. Some of the information gained by RSS intercepts gave an insight into ciphers used by the other German and Italian services.

5. Knowledge of spies’ training and arrival here so that they might often be used to our advantage.

Above all it enabled, or contributed to, extremely successful deception plans concerning our various misdirect ions as to what our military intentions were. The outstanding example, in our sights from the beginning, was the impression given that the 1944 invasion of the continent of Europe, would be in the Pas de Calais area, rather than Normandy.

The Secret Listeners by PAUL WRIGHT, G3SEM

This article is reproduced by permission from the RSGB. It reflects research Paul did for the BBC to produce the documentary “Secret Listeners” which you can watch here. The sudden death of a great friend of mine, Hugh Lawley, G6ZG, prompts me to try to achieve a little more recognition for a now diminishing group of radio amateurs who made a unique and seemingly invaluable contribution to British and Allied Intelligence during the second world war. With the showing on BBC2 last year of the television programme “’The Secret Listeners” (for which I had researched for more than two years), the story was revealed of how almost 1,500 British amateurs and other morse operators had served during the second world war as “Voluntary Intercepted* (Vi’s), after over 35 years during which virtually no detailed information had leaked out. But there are still many present-

Approach by RSS

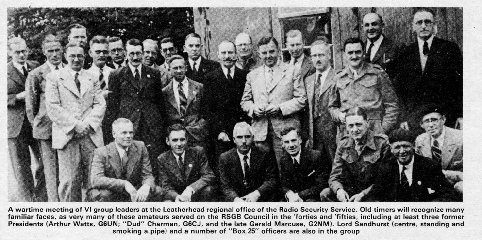

It began in 1939 when Arthur Watts, G6UN, the then President of the RSGB, was approached by Lord Sandhurst, an officer in the Security Service (MI5X to find out if radio amateurs (who were officially closed down on I September) could help in setting up a radio listening watch on behalf of the Radio Security Service. RSS was much concerned that enemy agents might try to set up mf air navigation beacons in this country to guide hostile aircraft, or possibly try to contact Germany by means of hf radio. Arthur Watts responded enthusiastically; he felt this was a golden opportunity for amateurs to show they could make a useful contribution during wartime—and indeed the idea of an amateur “listening watch” had been mooted during the first world war. Gradually, under oaths of secrecy, he talked to some of the leading dx and contest operators of the time; then, in spreading ripples, the bulk of amateurs with useful cw experience were roped in—or at least those who had not already been “called up1″or joined the Services as members of the 1932 Royal Naval Wireless Auxiliary Reserve (RNWAR) or the 1938 RAF Civilian Wireless Reserve (CWR). By spring 1940 this new and shadowy organization of Vi’s ensured that there were “secret listeners” spread all over the country.

The practical problems facing civilian spare-

The great discovery

The Vi’s, if truth is to be told, found no mf beacons and few genuine enemy spies in Britain. For from the outset of the war German agents, as they arrived in this country, were quickly located (for reasons that will emerge later) and often “turned” into double agents, controlled by British Intelligence in what became known as the “Double Cross” system, sometimes with British amateurs at the key of the German “suitcase” sets (which often required skilled adjustment before they could be made to work). But the Vi’s stumbled on to something infinitely more important than a few lone German spies would ever have been, a spreading network of German secret communications links between stations in Berlin, Hamburg, Vienna and Wiesbaden and outlying German Intelligence posts in occupied and neutral countries and in ships. Some were radio links with agents in the field, but many more were the busy circuits to the “Asts” and “KOs”—the main Abwehr and RSHA offices in the towns and cities. A few were dx circuits to North and South America. These stations used the techniques of “clandestine” radio: for example, callsigns were not linked and were frequently changed; out-

The Vi’s duly filled in their RSS log sheets and sent them by post to headquarters, which for a time was located in the cells of Wormwood Scrubs prison, but which soon became the cryptic POBox 25 that was in reality Arkley View, Barnet, in North London. Here RSS set up its discrimination and traffic analysis unit, manned in part by amateurs, to keep tabs on this interesting and growing German radio activity and to extract all possible signals intelligence from the logs before passing the coded messages to the Government School of Codes and Ciphers at Bletchley Park (Station X or “BP”), some 40 miles north-

For at first only the relatively low-

The German traffic

From about December 1940, BP began regularly to break into the vitally important transposition hand codes used for the majority of the messages to and from the Ast and KO out-

Furthermore, RSS was a creation of the Security Service, but those who were concerned with Intelligence activities on the Continent were members of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). With considerable reluctance, and following the intervention of Sir Winston Churchill, a joint arrangement was agreed between the different organizations. A special intercept station would be built and manned by operators drawn largely from the ranks of the Vi’s. As a result, from autumn 1941 many of the erstwhile radio amateurs were enlisted into Special Communications Unit No 3* and found themselves at Hanslope Park, a country estate conveniently near to BP and to Whaddon Hall, the secret service radio base. Even before the permanent station had been completed in May 1942, Hanslope Park became known as “The Farmyard”, and is still remembered half-

At the time, the former Vi’s, knowing nothing of the high-

Some, though by no means all, Vi’s had an inkling of the part they were playing in the war effort; others were left in ignorance on the “need to know” principle; virtually none was told of the deciphered contents of the messages. Some of those who joined SCU3 came to know a good deal more, and some were drawn into aspects of Intelligence that even today have not been fully revealed and are still subject to the Official Secrets Act. Military historians are just beginning to catch up with the role of Sigint between 1939 and 1945 but tend to concentrate on the code-

The former Vi’s themselves tend to shrug this off, recognizing that secret intelligence often needs to be kept secret; that they have much more to be thankful for than those British, American and European amateurs who gave their lives or suffered unspeakable hardships in serving their countries as civilians, Service personnel or in the Resistance movements. But it saddens me, as someone of a later generation than the Vi’s, that many of the names and callsigns that have appeared increasingly of late in the obituary column of Radio Communication have only rarely carried any hint of their work as Vi’s. Much of the material I collected during the making of “The Secret Listeners” is now with Pat Hawker, G3VA (whose help in putting together these notes I gratefully acknowledge). It is hoped later to publish a comprehensive account—in so far as this is possible—of the role of British radio amateurs in the greatest, if saddest, amateur radio contest of all time.

Pat Hawker G3VA writes

SCU3 was one of about a dozen Special Communication Units, under Brigadier Richard Gambier-

© The Secret Listeners

Website by CAMBITION